ITBFS: aka the Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

(…the pain on the outside of the knee)

In this series, I have discussed different types of overuse injuries and management of load when preparing for a race like the Gozo Half Marathon. Load management is key in a training program that is well graduated to the athlete’s fitness level and body mechanics.

In this final article, I will cover the second most common cause of knee pain in runners, and the most common cause of lateral knee pain (pain on the outside of the knee). I have suffered this injury myself and it plagues both the seasoned runner and the newbie training for his/her first race.

It tends to feel like a stabbing pain that develops slowly, usually within 7-10 minutes, as you run, until it stops you in your tracks.

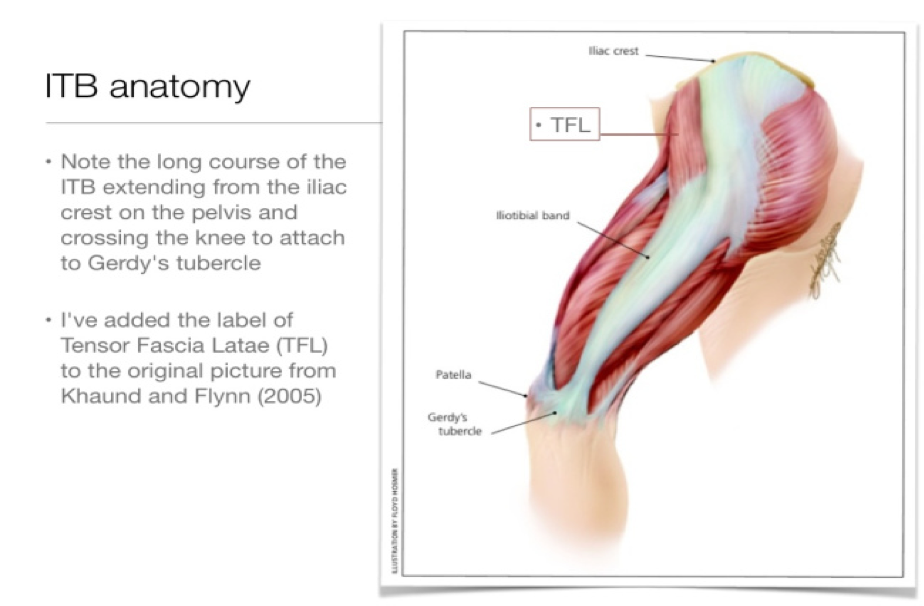

So, what is the Iliotibial Band (ITB)? There is debate as to whether the term ITB is correct in describing this structure or not, as it is not an independent structure but a mesh of connective tissue originating from multiple sites and inserting in as many others. Fairclough et al. in 2006 described it as a thick band of connective tissue spanning from your pelvic rim and originating from the gluteus maximus (GM) and a tiny muscle called the tensor fascia lata (TFL), down to your lower leg inserting into the Femur (thigh bone), Patella (knee cap) Tibia and Fibula (shin bones). Its main function is to passively control how much the knee moves inwards whilst the runner is in single-leg contact during the running cycle. It also stops the tibia moving forward and rotating inwards.

The name friction syndrome derives from the mainstream idea that the problem develops from rubbing of the fascia against the outside of the end of the femur (lateral femoral condyle). This friction causes the formation of a fluid-filled sac (bursa), pain and inflammation. Recent studies suggest it is more a question of compression of the ITB against a local fat pad that causes the pain (Balachandar et al. 2019).

Certain factors that could make you more susceptible to developing ITBS are:

- A naturally tight or wide ITB

- Weak hip abductors (e.g. Gluteus Medius) – causes pelvic instability and reduced control of the internal femoral rotation during the foot contact phase of running. This places excessive pressure and tightness on the ITB

- Overpronation of the foot – when the foot rolls inwards this causes rotation of the tibia, which causes extra tension on the ITB

- Overuse injury from excessive training

- Running on a cambered surface

- Leg length differences

(RS Sports Therapy, 2020)

What can be done to tackle this problem?

Firstly, it is important to prevent it from occurring. As always, prevention is key, so keep your glutes strong and focus on correct muscle lengthening after training. Follow a graduated program and try to listen to what your body is telling you. Machoism and hard-headedness lead only to people having to stop running, and transform a simple problem into a very big one.

If you already suffer from it I suggest you look for a physiotherapist knowledgeable in the treatment of overuse injuries. Discussion and assessment of your body’s biomechanics will provide you with a tailormade solution to thoroughly treat your problem.

What worked for me was the correct strengthening of my glutes using a theraband: sideways walking, glute bridges pushing out against a theraband, squats pushing out against a theraband and lots of core work involving side planks, front planks and reverse planks. Correct stretching after every session and proper footwear to meet the demands of running as related to my biomechanics were essential. I also tried to decrease my stride length and quicken my running cadence to about 80 – 90 steps per minute.

On a final note, keep running, stay injury-free, and most importantly enjoy it!

Simon Cilia